Canon 16-35mm f/4L IS vs. Canon 16-35 f/2.8L III - Which Lens is Sharper?

This page contains links to products, so if you find this site useful and use a link to make a purchase, I’ll get a small commission. As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. Thanks!

I have been using the Canon 16-35mm f/4L IS for a few years now, and it has been a reliable workhorse. Most reviewers consider it to be sharper than the Canon 16-35mm f/2.8L II, and it’s smaller and cheaper, so I never gave consideration to the bigger, faster, more expensive lens. The f/4 lens with image stabilization produces nice images, and I found it to be a worthwhile upgrade from the less expensive Canon 17-40mm f/4L I was using previously.

Lately, however, I have started to daydream (night dream?) about astrophotography and nighttime photography. Taking pictures of stars at night? Milky Way? Auroras? Yes please!

The problem with taking pictures at night is that it’s… at night. It’s really dark out. This means you might want a lens with a faster aperture than f/4 to minimize noise. The other potential issue with photographing the starry sky is something called “comatic aberration.” Camera lenses can suffer from varying degrees of comatic aberration, or “coma,” which causes stars to appear misshapen in your photos instead of round, especially at the edges of the frame. Lens aperture, sharpness, and the possibility of comatic aberration are all considerations when looking at lenses for night photography.

The philosophy of some photographers is to get multiple prime lenses at various focal lengths. A good prime lens can be small, fast, and sharp, but only at a single focal length (24mm, for example). With prime lenses, the manufacturer doesn’t have to make compromises to accommodate multiple focal lengths like they do with a zoom lens. The downside to prime lenses is that in order to cover multiple focal lengths, you have to carry multiple lenses.

My philosophy for landscape photography (though I do love tilt shift lenses for architecture) is to get a small number of fast, sharp zoom lenses so I can cover any focal length I need without carrying a bunch of different prime lenses. That will save space in my camera bag and allow me to spend more time taking photos and less time changing lenses. The question I had was: Is the Canon 16-35mm f/2.8L III able to capture sharp photos without comatic aberration, and provide fast wide-angle coverage?

When researching Canon’s 16-35mm f/2.8L III there were multiple websites where I encountered statements like “Canon’s 16-35 f/2.8 III is the same as the f/4 version, except bigger and more expensive, so most people should just get the f/4.” I also saw other research that claimed the new f/2.8 III was sharper, but I couldn’t find image any comparisons of the two lenses for the purpose of astrophotography, so naturally, I had to check it out for myself.

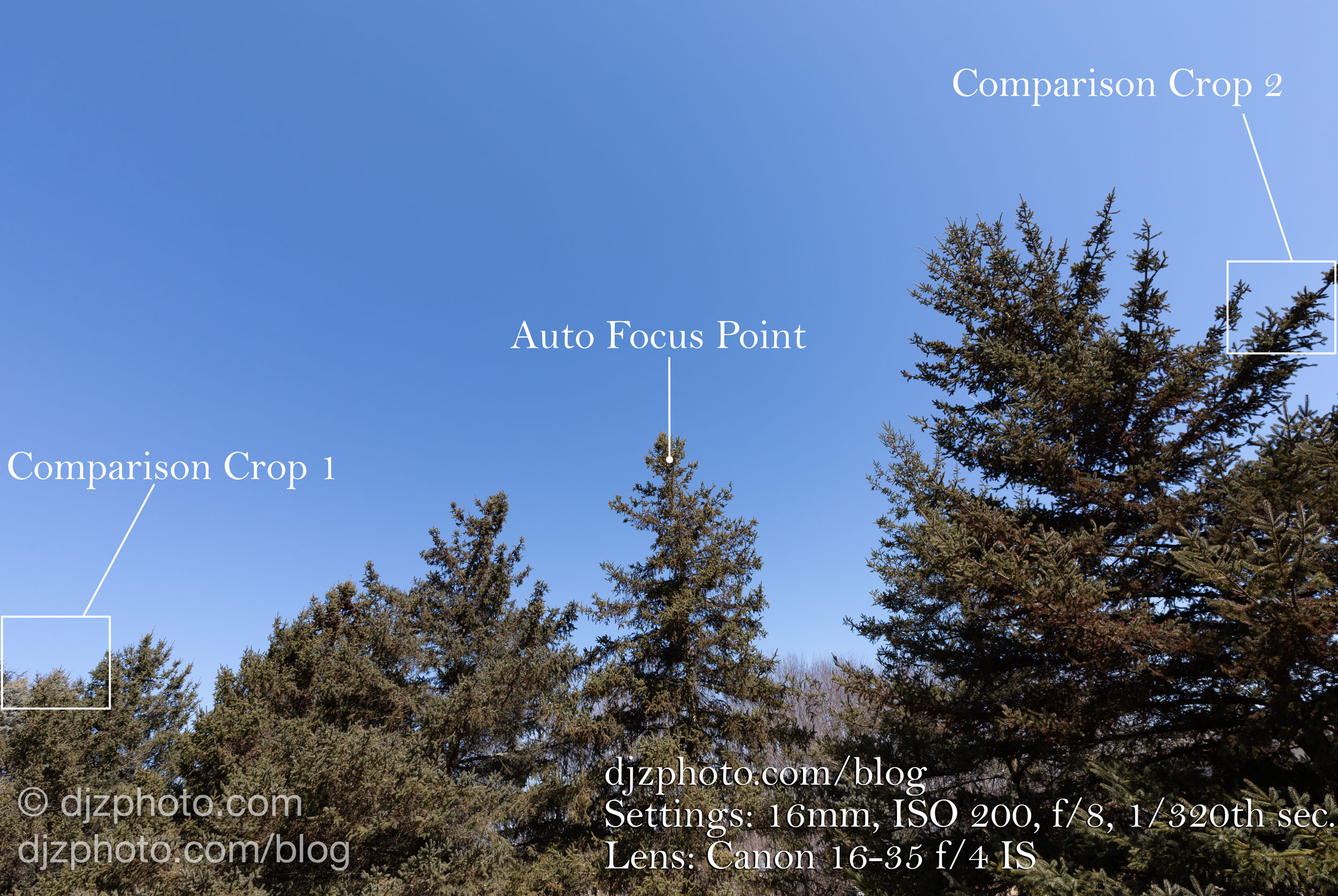

First, I wanted to compare the lenses for standard daytime photography at the wide end (16mm), where most lenses reveal the most distortion. I setup a tripod and took a picture of the same trees from the same spot, with the same settings for the two lenses: Canon 5D Mark IV, 16mm, ISO 200, f/8, 1/320th shutter.

Before I continue, please realize that I am going to be zooming in over 1000% in order to notice slight differences. Both lenses can certainly produce images that are print quality, without question. I just wanted to dig out the pixels to an extreme degree to see if one lens is slightly better than the other.

First, let’s look at the daytime shots.

Here we see two 16mm shots from the two lenses. Settings: 16mm, ISO 200, f/8, 1/320th sec.

Overall, it looks like two standard, sharp daytime shots. In these images I have labeled the areas that I’ll be zooming in to (Auto Focus Point, Comparison Crop 1, and Comparison Crop 2).

Most people wouldn’t notice a difference in sharpness in the above two images.

Next, let’s zoom in to the center of the image, where I pointed both lenses at the top of a tree to autofocus.

Nothing substantial yet, still just looks like two sharp daytime photos at the center of the image. Still pretty difficult to see any difference between the two.

Next, let’s take a look at where lots of lenses tend to reveal their weaknesses… the edges. We can start with Crop area 1 on the left side of the frame.

I was surprised at how sharp the f/2.8L III lens was at the edges in crop area 1 compared to the f/4L! I wasn’t sure if there would be much difference, but the clear winner here was the f/2.8 III, hands down. Again let me reiterate that most people would not notice this if you were looking at the whole image, it’s only when we zoom in to 1300% that these differences become apparent near the edge of the frame.

Next, let’s take a look at crop area 2 on the right side of the frame.

In crop area 2 the f/2.8L III still wins but perhaps less dramatically. It’s most noticeable if you look at the needles on the right side.

Next, let’s take our lenses to a slightly more challenging environment: photographing stars at night.

First, we have the whole scene comparison shots. I added in constellations for reference, and for fun (because why not?). It’s worth noting that the f/2.8 III has an obvious advantage in that it can open up to f/2.8 and capture light twice as fast as the f/4L lens, so to keep it fair, I set both lenses to f/4 and auto focused on some of the house lights across the water.

Settings: Canon 5D Mark IV, 16mm, ISO 3200, f/4, 10 second exposures (stacked in Starry Landscape Stacker to reduce noise)

In those whole scene comparisons you wouldn’t notice any difference between lenses. So let’s zoom in to about 1000% at the center, above the constellation Serpens Caput.

I didn’t see much of a difference at the center, especially considering this is a tiny section of a 30-megapixel image. Next, let’s zoom in to the edges and see what happens. We can start near the feet of the constellation Hercules.

In the above images we can see a slight example of “coma” (comatic aberration) in the f/4 image now that we’ve zoomed in to an extreme degree near the left side of the overall image, near Hercules’ feet. Even though you wouldn’t see it when looking at the whole picture, when we look closely we can see the the stars in the f/4 lens image seem to be shaped like little paper airplanes that are leaking pixels, instead of round stars as they should be. The stars in the image produced with the f/2.8L III lens (set to f/4 to make the comparison even) are rounder and sharper. Since it is a 10 second exposure and we are zoomed in over 1000%, the star movement is slightly apparent, but I was pleased with how sharp the stars were on the f/2.8 III, and happy that it exhibited virtually no coma.

Let’s check the right side of the image near the constellation Virgo.

On the right side of the frame, near the constellation Virgo, the f/2.8L III lens is again the winner. The stars are sharp, round points that have moved slightly over the course of 10 seconds, but the f/4’s stars are slightly blurry from edge softness and shaped like little bats due to the minor comatic aberration going on.

While these slight differences are probably not noticeable to someone looking at the whole image, it is good to know that Canon clearly put a lot of effort into making the 16-35mm f/2.8L III lens optically superior to all of it’s previous 16-35mm offerings, with edge to edge sharpness and virtually no comatic aberration. This is reassuring if you are looking to make large prints of your photos, and a high quality lens with exceptional sharpness will be more able to support a higher megapixel camera in the future. In 2004, Canon’s EOS-1D Mark II was 8 megapixels, and the EOS-1D was only 4 megapixels in 2001! Camera companies in the not-so-distant past were making full-frame lenses for cameras that were either 35mm film or low-megapixel digital. But now that 20, 30, and 50 megapixel camera bodies are standard and meticulous people (like me!) are analyzing lens sharpness at 1300% zoom levels, lenses have to be able to support all those megapixels with high quality optics. What’s the point of all those megapixels if the lens isn’t sharp?

Hopefully you found this helpful in comparing a couple of Canon’s wide angle zoom offerings. I learned a little bit while making this comparison page, and that’s always a good thing. =)